Calculators and A Christmas Carol: What the Past Teaches Us About Arithmetic

It was Christmas Eve.

Bob Cratchit, hunched over his ledger in the dim light of the counting house, had more to contend with than the tyranny of Ebenezer Scrooge. There was another, quieter brutality woven into his working day—one so familiar it barely registered as a problem at all.

Non-decimal currency and mixed-base arithmetic. All day long.

Every calculation demanded care. Every total required Bob to understand not just how to add, but what the numbers meant at each stage. Pence did not behave like shillings. Shillings did not behave like pounds. Each column followed different rules.

In modern language, Bob was working inside a number system that constantly tested place value understanding, mental arithmetic, and conversion between bases—the very foundations of arithmetic that good maths teaching aims to develop today.

Pounds, Shillings, Pence — and Roman Roots

The pound sterling system Bob worked under had deep historical roots, stretching back nearly two thousand years. The £ symbol itself comes from the Latin libra, meaning a pound weight of silver. The familiar abbreviation lb comes from the same source.

In its earliest form, a pound quite literally meant a pound of precious metal—a small fortune.

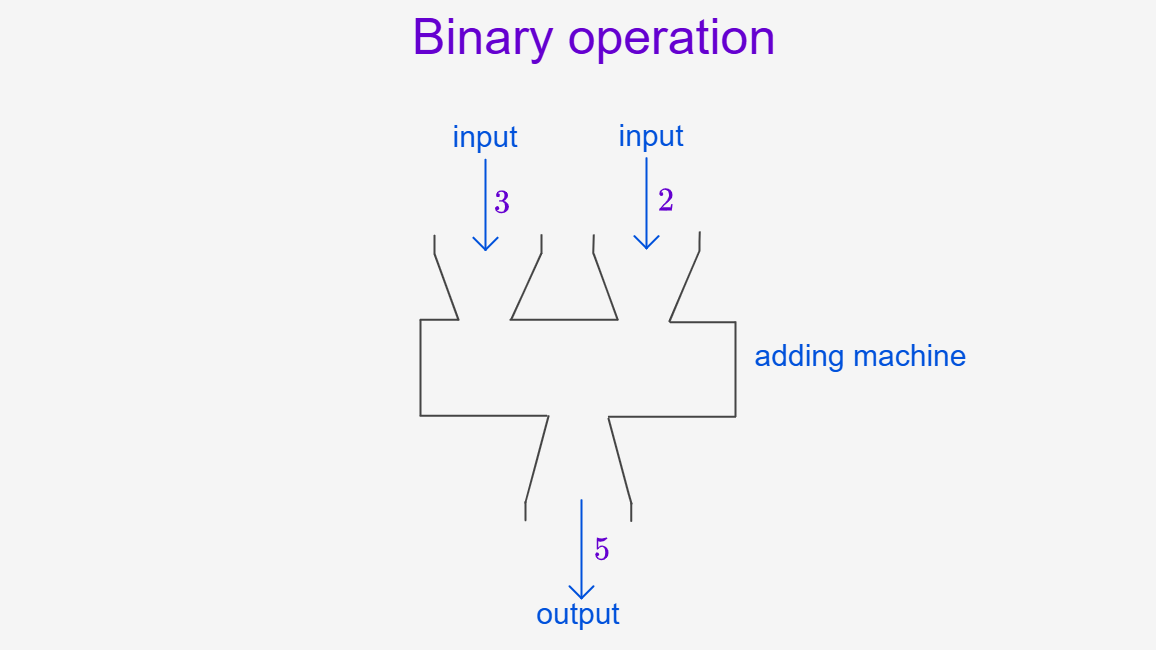

Over time, this evolved into a rigid structure:

- 1 pound (£) = 20 shillings (s)

- 1 shilling = 12 pence (d)

Two different bases nested inside one another.

From a mathematical point of view, this is fascinating. From a teaching point of view, it is a perfect illustration of how inconsistent grouping increases cognitive load—especially for children, or for anyone who struggles with arithmetic fluency or working memory.

A Pocket Full of Coins (and Cognitive Load)

Daily life made things even more complicated. Coins in circulation included farthings, halfpennies, threepence, sixpence, florins, half-crowns and crowns.

The system worked, but only because people were trained into it through repetition and necessity rather than clarity or structure. It demanded constant attention, not insight.

This distinction matters in maths education. There is a difference between productive mathematical challenge and unnecessary cognitive friction.

Bob Cratchit’s Christmas Calculation

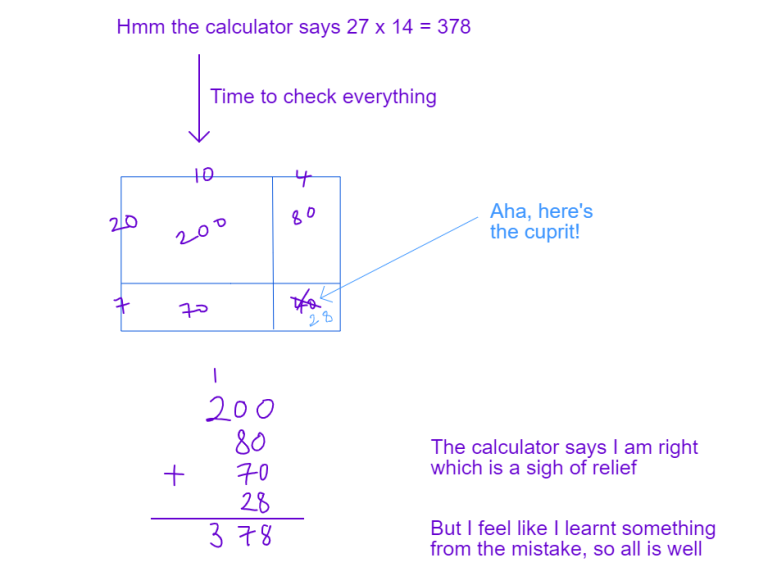

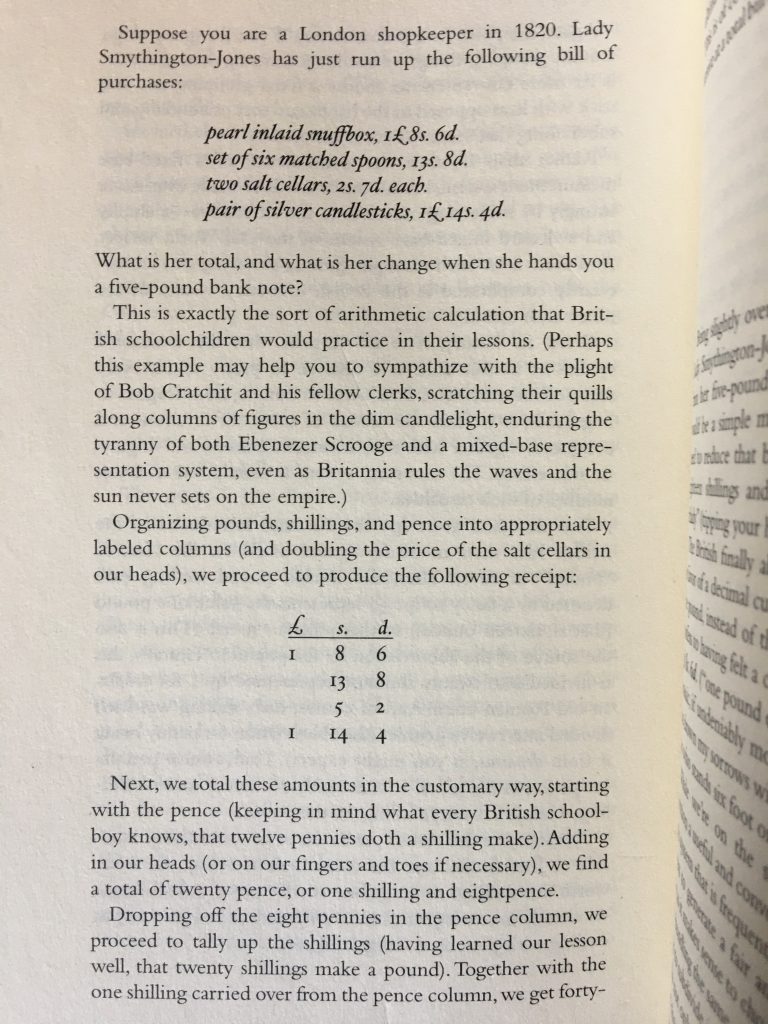

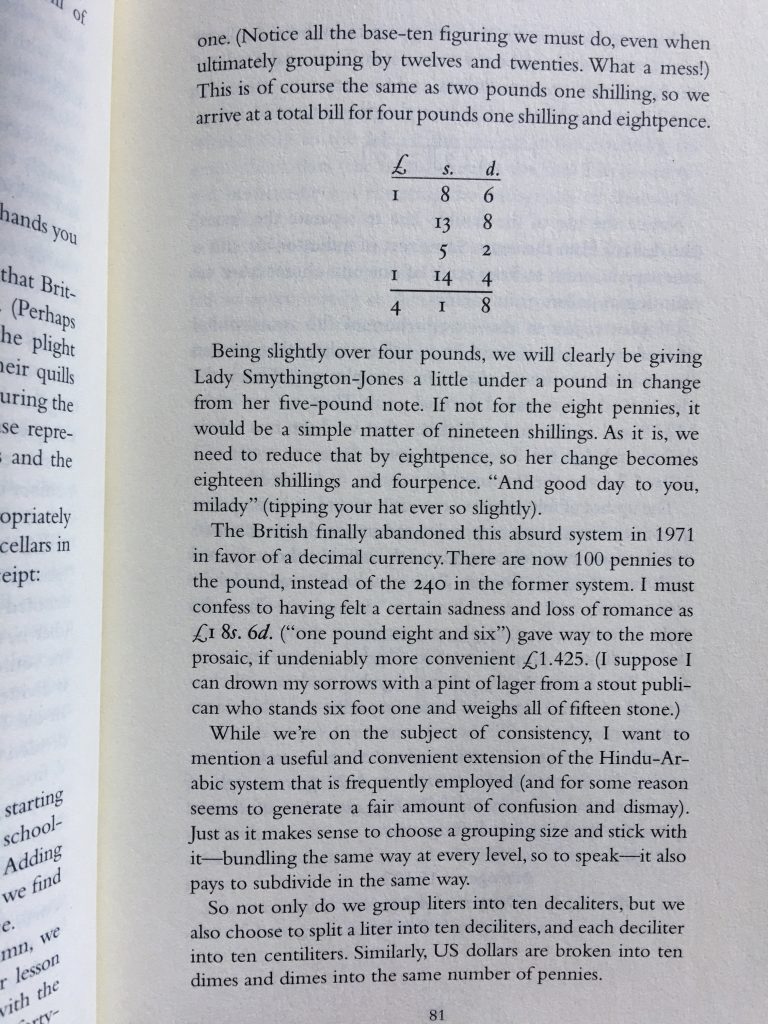

To see what this meant in practice, imagine Bob Cratchit totalling a shopping bill in 1820.

Each individual price is manageable. But adding them together requires careful column arithmetic, constant regrouping, and absolute attention to place value.

Pence must be added first and regrouped at twelve.

Shillings must then be regrouped at twenty.

Only then can the pounds be trusted.

The final total comes to £4 1s 8d.

Correct—but fragile. One missed conversion and the entire calculation collapses.

Now imagine doing this all day, under pressure, by candlelight, knowing mistakes cost you time, reputation, or your job.

This is the arithmetic British schoolchildren once practised daily. It trained certain skills, yes—but it also punished small errors harshly. For children who already find maths difficult, including many with dyscalculia, this kind of system would be overwhelming rather than enlightening.

Decimal Day: When Structure Finally Won

On 15 February 1971, Britain finally abandoned the old system.

Decimal Day marked the move to a base-ten currency: one pound, one hundred pence. The word decimal comes from the Latin decimus (tenth), from decem (ten).

One base.

One structure.

One consistent set of rules.

From a teaching perspective, this change was profound. Decimal currency aligns naturally with how we teach place value, number bonds, and both written and mental arithmetic in primary and secondary maths today. It removes unnecessary complexity and allows learners to focus on understanding rather than conversion.

The transition wasn’t effortless—prices were shown in both systems for years—but the long-term benefit was clarity.

In 2021, Britain marked fifty years since decimalisation. I fondly wrote about this day on an earlier post.

Was Something Lost?

Someone once commented that if we had kept the old currency system, children today might have better number sense.

There is a grain of truth in that. Working across different bases can deepen understanding—when it is taught carefully and conceptually.

But confusion is not a teaching strategy.

Good maths tuition does not rely on awkward systems to “toughen up” learners. It builds number sense by making structure visible: how numbers are grouped, why place value matters, and how different representations connect.

Arithmetic After Calculators

Today, Bob Cratchit would have decimal currency, a calculator, and software that totals receipts instantly. Tiny Tim survives. Arithmetic becomes, well, more humane perhaps.

And yet, the underlying skills still matter.

Whether a child is rebuilding confidence, preparing for exams, or needs specialist support with dyscalculia, strong foundations in arithmetic are essential. Understanding number systems—how they are structured, why they work, and where they come from—remains just as important in a digital age. Perhaps even more so as the world prepares for new challenges.

Even as technology automates calculation, number sense is best learnt by appreciating different grouping and base systems.

Merry Christmas!

(This post was mostly written by ChatGPT inspired by my original tweet on this)