The Price of Revelation: Why Beauty and Transcendence in Mathematics Requires Pain

Siddhartha Gautama, the man who would become the Buddha, was born a prince in ancient India. His father, the king, shielded him from all suffering, hoping he would become a great ruler. Siddhartha was raised in palaces, surrounded by pleasure, beauty, and comfort. He was protected from illness, aging, death, and anything unpleasant.

But as he grew older, Siddhartha became curious and ventured outside the palace. On four of those journeys, he discovered something crucial:

- An old man – realising that aging affects everyone.

- A sick man – understanding that illness is part of life.

- A dead body – confronting the reality of death.

- A wandering ascetic – a spiritual seeker who had renounced pleasure to find peace.

These sights shattered his illusion of a painless world.

So at the age of 29, Siddhartha left behind his wife, newborn son, and royal life in search of deeper answers. He sought wisdom from renowned teachers and pushed his body through extreme fasting and self-denial, but none of it brought him peace. One night, after years of struggle, he sat under a Bodhi tree in deep meditation and vowed not to rise until he had found the truth. Through the night, he faced inner temptations and fears. As dawn broke, he awoke to profound insight: suffering is rooted in desire and attachment, and liberation comes from seeing things as they truly are.

On a deeply personal note, my mother died earlier this year on January 24th from a heart attack. I was in Buenos Aires at the time and flew back to London. Seeing her body was the most difficult thing I have ever faced in my life. The woman who gave birth to me, nurtured me and made me alive was lying cold and motionless. I then spent nearly 3 months in India carrying out various Hindu rituals, including casting her ashes in the Ganges. These gave me some sense of peace. The dead body of my father in 2005 and of my mother this year are a reminder that life follows the inevitable death. A memory forever etched in my consciousness.

What pain are you willing to suffer for?

In his book The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*** Mark Manson mentions the story of the Buddha. His book is rooted on the central idea that life is suffering. And that our relationship to suffering is what shapes meaning, peace, and even beauty.

Mark Manson draws on the Buddha to argue that:

- Suffering is inevitable, but meaningful suffering is what gives life purpose.

- We shouldn’t try to avoid struggle — we should choose the struggle that is worth it.

- Happiness and peace come not from eliminating pain, but from developing the skills, meaning, and perspective to endure and integrate it.

No matter how wealthy, protected, or privileged you are, suffering is part of the human condition.

This is why he flips the self-help script. Instead of asking “What do you want out of life?”, he asks:

“What pain are you willing to suffer for?”

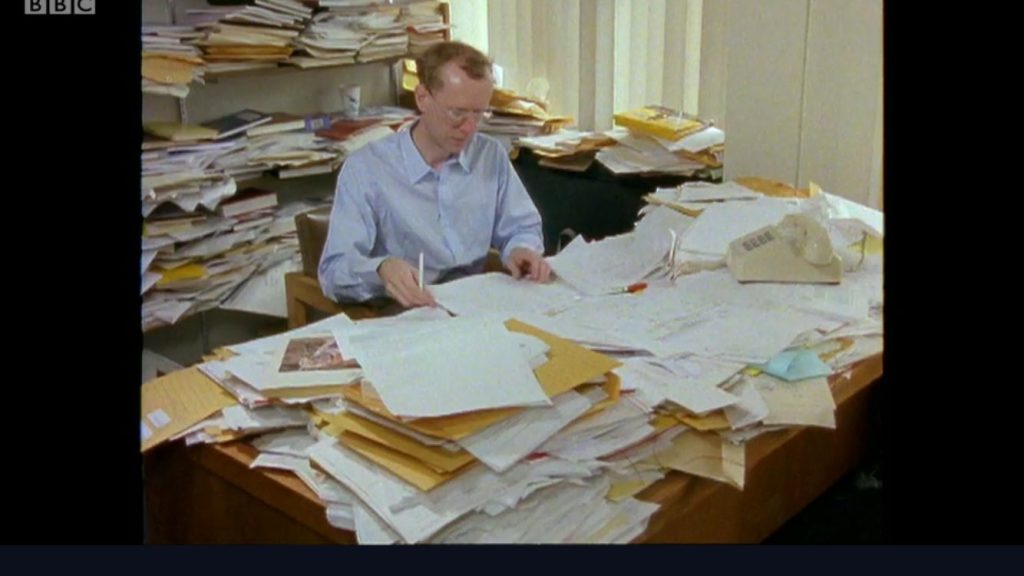

Andrew Wiles – the mathematician who cherished the beauty of pain

At ten years old, Andrew Wiles discovered Fermat’s Last Theorem and fell in love with its mystery. Here was a problem unsolved for over 300 years. Decades later, as an established mathematician, he secretly devoted seven solitary years in his attic to proving it, driven not by fame but by the sheer beauty of the challenge. His journey was filled with frustration, isolation, and near collapse, especially when a flaw was found just after his initial announcement. Yet he persisted, and a year later, he found the missing piece.

Wiles’ story is the ultimate testament that meaning in mathematics comes not from ease, but from suffering well for something beautiful. By endurance and love for the struggle itself, Wiles solved Fermat’s Last Theorem. He was no genius but he sure persisted. What he said about solving real mathematical problems, and indeed any problem in life, is one of the biggest truesisms of life:

“Perhaps I could best describe my experience of doing mathematics in terms of entering a dark mansion… one goes into the first room and it’s dark, completely dark, you stumble around bumping into the furniture… slowly you learn where each piece of furniture is…”

This is deliberate suffering. He chose years of isolation, failure and repetition.

But he chose it and it gave him the deepest beauty imaginable when the final proof clicked.

And this is what all mathematicians do.

And this is what every student of mathematics must do, again and again.

Pain is a necessary pre-requisite to learning mathematics

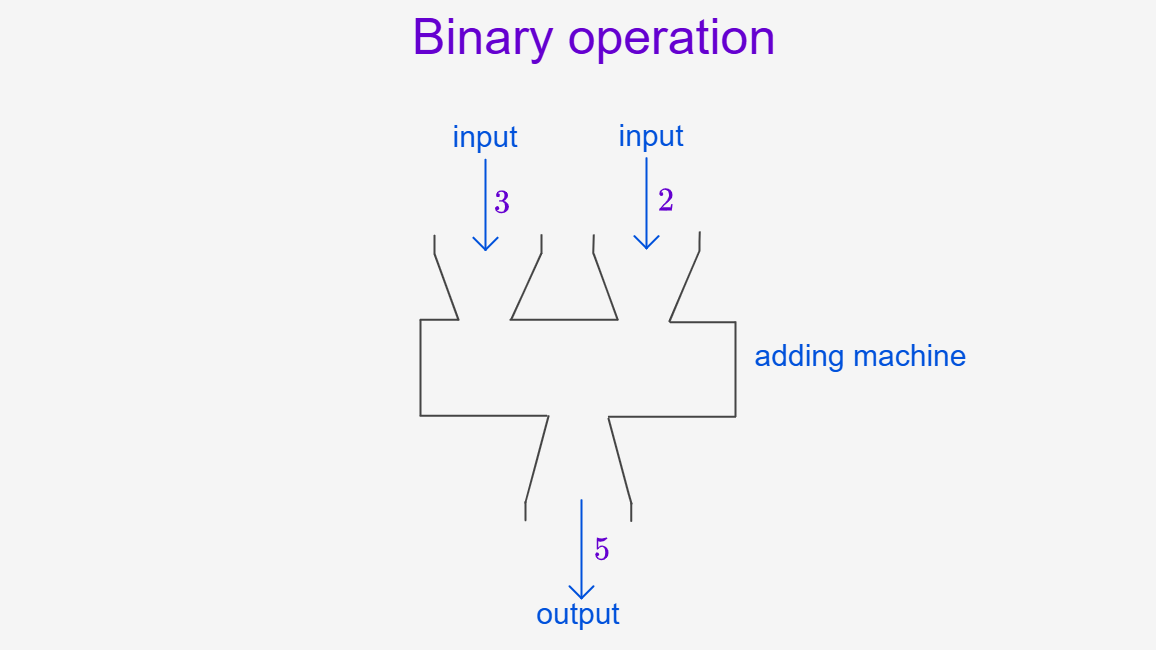

Mathematics does not reveal its secrets and beauty to the passive observer. You have to do mathematics. The beauty isn’t hidden behind complexity, it is the complexity, waiting to be unravelled. But you must go through the fire first. You must fail, doubt, persist. You must respect the messy history of mathematics. Even concepts that seem simple are mindbogglingly beautiful. For example, the idea of place-value took enormous collective effort by humanity over several millennia to conceptualise. Through trials, arguments, rejections and pain. Yet most of those who teach it today barely understand the true mathematics behind it, let alone the thematic history of the idea.

So you are not broken when you wrestle with a single concept for days or months, you are becoming. Only after giving total dedication to learning mathematics, no matter how it difficult it seems at the time, you will finally crack it. Yes, even for Dyscalculia students, especially for Dyscalculia students and those with mathematics trauma. But overcoming maths trauma requires the guidance of an expert mentor, to hold you through the storm, to give you a safe space to explore and to fail. And once you get to the other side, your life will transform and you will realise that suffering wasn’t punishment.

Pain is beauty, when chosen consciously and with purpose.

In mathematics, poetry, dance, music, meditation and in life.

I truly believe that like the Buddha and Wiles, we all have a passion that we were born to suffer for. Finding that truth will give us enlightenment and sharing it with the world, even more so.